What are Smart Materials?

There is no established definition of “smart” or “intelligent” materials. Many argue they are substances that respond to external stimuli (change in temperature, pressure, electric or magnetic field, etc.) and produce useful responses. However, this would also include common sensing substances like piezoelectric materials or shape memory alloys, which some scientists categorize as “smart” materials. However, it is more useful to focus on the response rather than the material itself.

According to NASA, smart materials are specially designed materials that can respond intelligently to their surroundings, recall many shapes, and reconcile with certain stimuli.

According to some sources, there are not actually any “smart” materials; rather, there are just materials with specific fundamental properties that may be used to create objects, machines, or buildings that behave intelligently. This behavior consists of reactions to outside stimuli, including self-sensing, self-actuating, self-healing, shape-changing, and self-diagnosis. The name “smart material” was not used until the 1980s, leading many to believe that the technology behind it is relatively new. However, numerous products, such as photochromic eyewear, have been used to show smart behavior for decades.

Importance of Smart Materials

Ceramics metals, polymers, and recently developed smart or advanced materials are the four primary types of material. Advanced materials are becoming more popular since they have more technical uses.

Smart materials are the foundation of most cutting-edge hybrid equipment since they can adjust some of their physical and mechanical characteristics. Computer generations have been revolving around semiconductors since vacuum tubes gave way to smaller electronic chips [1]. On the other hand, biomaterials made it possible to interact with biological structures. Similarly, nano-engineered materials perform better than their bulkier equivalents [2]. As a result, the use of smart or intelligent materials will increase dramatically in areas such as civil engineering, automated systems, medical equipment, and industrial appliances.

Smart materials are now required for many projects because of their capacity to modify their characteristics when subjected to external stimuli. They are one of the outstanding materials because of their reversibility, characterized by their environmental sensing, mending, and adaptability. Mechanical stress, temperature, hydrostatic pressure, strain, electric current, magnetic field, pH, and chemical effects are only a few examples of the variables that can alter the size, color, moisture content, fragrance, and viscosity of a flow [3]. Thus, by utilizing the parameters mentioned above, applications for the smart material can be fulfilled for sensors, actuators, drug delivery and many other sophisticated areas.

Classification of Smart Materials

Smart materials are broadly classified into active and passive categories:

Active Smart Materials

Active smart materials can transduce energy by changing their properties or geometry when subjected to thermal, electric, or magnetic forces. This characteristic enables the production of force transducers and actuators using active Piezoelectric materials, shape memory alloys (SMAs), electoastrictive materials, and magnetoastrictive materials.

There are further classified into two categories. When subjected to outside influences, the first kind can modify its features, as with photochromic glasses that can change color when exposed to sunlight. The second category can transform energy from one form to another in the realms of thermal, mechanical, chemical, electrical, optical, and nuclear. Examples of these devices are photovoltaic (convert light energy into electric energy) cells, LEDs (convert electric energy into light energy), etc.

Passive Smart Materials

Passive smart materials are those that do not have the ability to convert energy. Examples of materials that may transport energy include fiber optics, which can transmit electromagnetic waves. Instead of being employed as actuators or transducers, these materials are used as sensors and transmitters.

Types of Smart Materials

Piezoelectric Materials

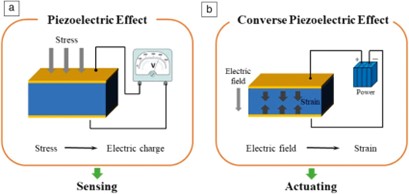

Piezoelectricity is typically an electromechanical phenomenon that couples the elastic and electric fields (static and dynamic coupling). The direct piezoelectric effect occurs on applying mechanical stresses or pressures that, as a result, generate charges or voltages. The opposite piezoelectric effect is the ability of electric charges or fields to cause mechanical stresses or strains in a material as the external electric source is applied (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Piezoelectric effect, (a) sensing, (b) actuating.

According to configurations and designs, or with/without mechanical amplifications or deductions through lever systems, the actuation stroke can be as small as nanometers or as large as millimeters.

Table 1: Different Piezoelectric materials types.

| Natural crystals | Quartz, ammonium phosphate, Rochelle salt, etc. |

| Noncrystalline materials and Textures |

Rubber, paraffin, etc. Wood, bone, etc. |

| Synthetic piezoelectric materials | (a) Piezoceramics: lead lanthinum zirconate titanate, barium titanate, lead zirconate titanate, lead niobrate, etc.

(b) Crystallines: lithium sulfate, ammonium dihydrogen phosphate, etc. (c) Polymers: polyvinylidene fluoride, etc. |

Applications of Piezoelectric Materials

The applications of piezoelectric materials include both sensors and actuators as follows:

- Piezoelectric motors

- Actuators in different areas (printers, speakers, etc.)

- Sensors (ultrasound signal detection, precision drives and

control etc.) - Piezoelectricity buzzers & microphones

- Piezoelectric igniters (spark generation)

- Nanopositioning in AFM, STM

- Micro Robotics

Electrostrictive Materials

Electrostrictive materials share many of the same characteristics as piezoelectric materials, but they vary their mechanical characteristics in a square relationship to the strength of the electric field, always causing displacements in the same direction. As a result, the induced strain varies irrespective of the direction of the applied field, and the field’s reversal results in identical deformation (direction and amplitude). The ferroelectric family includes piezoelectrics and electrostrictors.

In electrostrictive materials, ions are moved from their initial places when they are subjected to an electric field, increasing their size. Additionally, piezoelectric materials exhibit this property but there are some significant differences.

Table 2: Differences in electrostrictive and piezoelectric materials

| Electrostrictive Materials | Piezoelectric Materials |

| Nonlinear (quadratic strain) relationship between changing electric field size and strength [4]. | Linear relationship between the strength of the electric field and changing size [5]. |

| Their hysteresis is lower than that of piezoelectric materials at room temperature and quantitatively greatly depends on temperature [6]. | They have a hysteresis of above 10%. This value does not significantly change with temperature changes at room temperature [7]. |

| Compared to piezoelectric materials, they have a higher electrical capacitance. | Temperature-dependent strain stability of these materials is comparable to that of electrostrictive materials. |

Niobate-lead titanate (PMN-PT), lead manganese lead lanthanium zirconate (PLZT), Potassium niobate (NKN), potassium sodium bismuth titanate (KNBT), lead magnesium niobate (PMN), lead zirconate titanate (PZT), barium titanate (BaTiO3), lithium niobate (LiNbO3), etc. are the examples of electrostrictive materials.

All dielectric materials often exhibit electrostriction, although it is weak because of the greater first-order piezoelectric action. Therefore, for the majority of practical purposes, a smaller second-order electrostrictive effect is disregarded during the development of piezoelectric applications. On the other hand, materials with high dielectric constants (high polarizations), such as relaxor ferroelectrics, can show extremely high electrostrictive stresses. The spontaneous polarization in a relaxor ferroelectric steadily decreases with rising temperature instead of disappearing at a certain Curie temperature, just like piezoelectrics.

Applications of Electrostrictive Materials

- Actuators: Electrostrictive materials can be used as actuators to convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. They are used in a variety of applications, such as robotics, precision positioning systems, and fluid control valves.

- Optical devices: Electrostrictive materials, such as tunable lenses and optical switches, can be used in optical devices.

- Vibration dampers: Electrostrictive materials can be used in vibration dampers to reduce the vibration and noise generated by machinery and structures.

- Energy harvesting: Electrostrictive materials can be used in energy harvesting applications to convert mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- Sound generators: Electrostrictive materials can be used as sound generators in applications such as alarms and speakers. By applying an electric field, the material can be made to vibrate and produce sound.

Pyroelectrics Materials

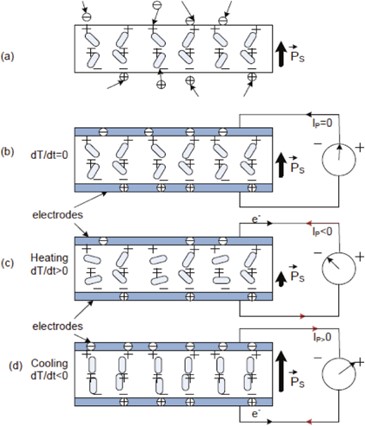

Pyroelectrics become electrically polarized in response to temperature variations (Figure 2). Typical pyroelectric materials include lead zirconate titanate, lithium tantalate (LiTaO3), triglycine sulfates (TGS), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), barium strontium titanate, and barium strontium niobate. Ceramics are widely used due to their easy availability, inexpensive cost, and high-temperature resilience. However, their brittleness is a negative aspect. Although polymers like PVDF and its tri-fluoroethylene copolymer offer durability, performance is still lacking in quality. Pyroelectrics are a common technology for detection and targeting applications because they are sensitive to infrared radiations [8].

Figure 2: Pyroelectrics material behavior while (a) spontaneous polarization, (b) constant temperature, (c) during heating and (d) during cooling.

Applications of Pyroelectric Materials

Pyroelectric materials have a variety of applications in different areas, some of which include:

- Temperature sensors: Pyroelectric materials can be used as temperature sensors to measure temperature changes in materials or objects. They are used in thermography, where they are used to measure temperature changes in buildings, machinery, and other structures. They are used in fire detection systems.

- Infrared detectors: Pyroelectric materials are commonly used in infrared detectors to detect temperature changes caused by infrared radiation. These detectors are used in security systems, motion sensors, temperature sensing devices, and other applications.

- Energy harvesting: Pyroelectric materials can convert heat energy into electrical energy and are used in energy harvesting applications, such as in thermoelectric generators that convert waste heat into electricity.

- Non-destructive testing: Pyroelectric materials are used in non-destructive testing applications like thermal imaging and materials testing for defects or flaws.

Shape Memory Alloys

Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs) are intelligent materials that have at least two fundamental phases that may change depending on the temperature or stress applied. They can recall their original shape from the austenite phase, allowing them to regain it when distorted. This mechanism, known as shape memory transformation, changes the solid’s atomic structure and microstructure [9].

Researchers and metallurgists have examined the impact of a wide range of factors on the physical characteristics of SMAs, including the addition of new materials to binary SMAs, mechanical treatment, heat treatment, surface improvement, various cooling techniques, and different sample preparation methods.

These smart materials can display a variety of properties, including thermoelasticity, superelasticity, and damping capability, demonstrating their distinctiveness.

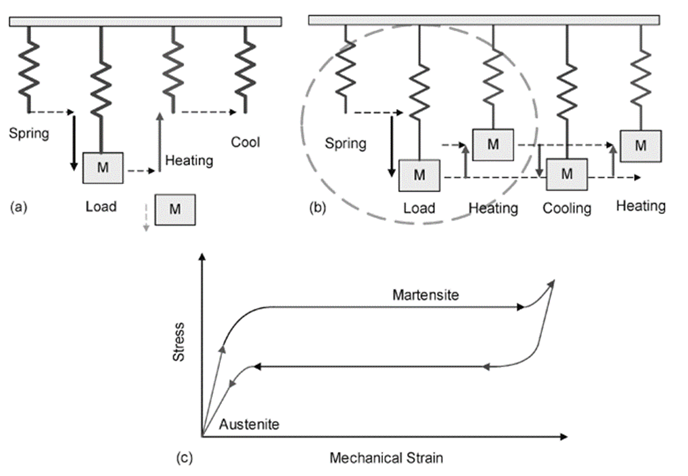

The three basic shape-memory effects are the one-way, two-way, and pseudoelasticity (or superelasticity) effects. Figure 3 shows different effects in SMAs.

The one-way effect plastically deforms an SMA in the martensitic state and regains its original shape at a higher temperature. There are two yield points in Ni-Ti alloys, which can be especially helpful in these materials. The yield point of this alloy is both extremely low and extremely high [10]. Heating can readily recover deformations over the first yield point but cannot recover deformations above the second yield point. For copper-based alloys, recoverable deformations can reach as high as 3-4%, while Ni-Ti alloys can reach as high as 6-8% [11].

The two-way effect is an effective approach to converting thermal energy into mechanical energy. In the case of an SMA in the martensitic state, applying the same force while heating above the martensitic transition temperature will decrease the strain in the alloy. The same stress will exert less strain on an austenitic than on a martensitic material. The austenitic state’s reduced elasticity is the reason for this phenomenon. SMAs are beneficial for many applications because the force produced while switching between the two states is fairly large.

The third effect is pseudoelasticity (or superelasticity) of SMAs, which only manifests when the SMA is just over its transition temperature. An alloy can undergo a stress-induced martensitic transformation when it is in the austenitic state. When the tension decreases, however, because the material is above its transition temperature, ambient thermal energy changes the martensite back into austenite. The alloy has a particularly springy or rubber-like elasticity due to its abrupt transformation back into its original austenite shape. The SMA can recover strain beyond what is possible for most materials because of this phenomenon. Ni-Ti wires can repeatedly recover strains of up to 5%, however fatigue is an issue [10].

The research for novel alloys that exhibit the shape-memory phenomenon is still ongoing. Recent patents have shown alloys with less nickel and titanium, including copper, zinc, and aluminum.

Figure 3: SMA different effects, (a) one-way, (b) two-way, and (c) pseudoelasticity.

Applications of Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs):

SMAs have been employed in several applications across numerous sectors. In addition to the flexible eyeglass frames mentioned above, they can be utilized in bioengineering projects like dental wires for braces, metal plates to repair shattered bones, and tools to clear blocked veins and arteries.

SMAs can be used in architecture to design self-adaptive buildings that can react to changes in the climate, including those brought on by wind, temperature, and light.

SMAs have potential uses in aviation and space vehicles since they are lighter and can help conserve energy compared to heavy mechanical actuators. They can also be utilized as actuators due to their ability to alter form.

Magnetostrictive Materials

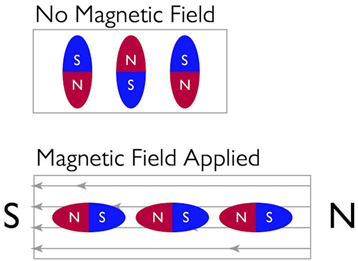

These materials are characterized by the induction of mechanical strain in reaction to the magnetic field and vice versa. This characteristic qualifies the material for use in sensors and actuators. Terfenol-D is a popular magnetostrictive substance. Nickel and alloys like Fe-Ni (Permalloy), Fe-Al (Alfer), Fe-Co, Co-Ni, and Co-Fe-V (Permendur) also show magnetostrictive attributes. Other magnetostrictive materials include ferrite, rare earths, and their alloys and compounds.

Magnetic constriction, like electrical constriction, is a second-order (quadratic) action, meaning that the amount of strain caused is proportional to the square of the magnetic field applied. As a result, the direction of the applied magnetic field has no bearing on the strain that is produced, and when the field is reversed, the same deformation (direction and amount) takes place.

Figure 4: Magnetic field applied to magnetostrictive materials causes them to alter form.

Rheological Smart Fluids

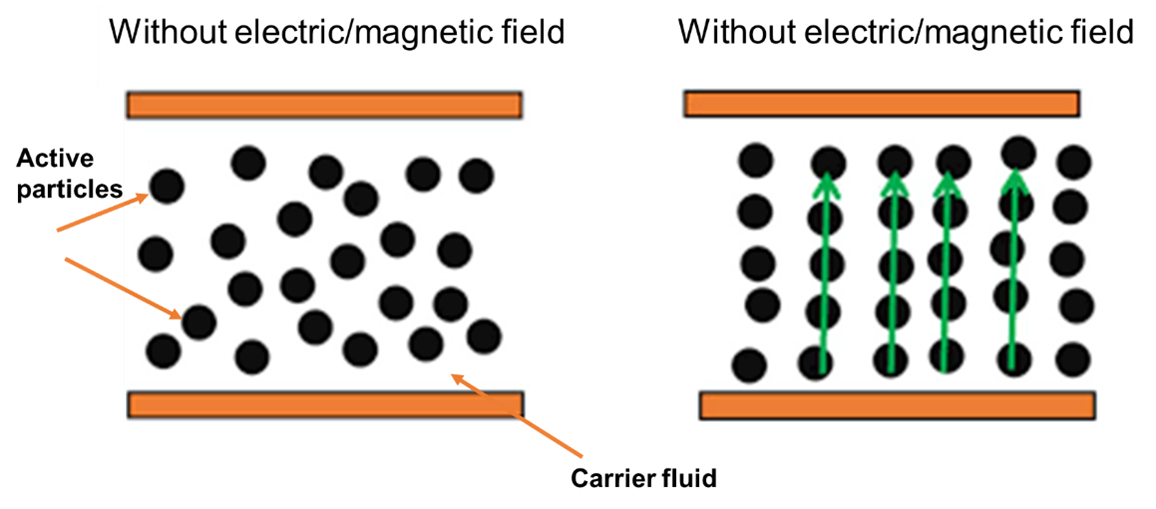

Temperature and pressure typically affect the kinematic viscosity of most fluids. However, the molecular makeup of electro and magnetorheological fluids governs their viscosity by ambient electric or magnetic fields. This means that the viscosity of an electro and magnetorheological fluid changes without affecting the fluid’s temperature or pressure. Electrorheological, magnetorheological, and ferrofluids are three categories of active rheological fluids. These fluids’ physical characteristics are altered when introducing an electrical or magnetic field. An electric or magnetic field causes the yield stress comprising micron-sized particles distributed in a carrier liquid (often oil).

Figure 5: Viscosity changing phenomenon of electro/magnetic fluids.

Electrorheological Fluids

Electrorheological fluids undergo significant property changes in response to an adequate electrical field. Electrorheological fluids often act like regular Newtonian fluids. The electrorheological fluid cannot flow freely due to the linear structures that emerge when an electric field is applied. Additionally, electrorheological fluids only take a few milliseconds to change their yield stress and viscosity characteristics. Thus, electrorheological fluids can quickly transform from a liquid to a structure resembling solids, which is extremely useful in engineering applications.

The major suspension particles are polymers, alumina, silicates, metal oxides, and other materials. Since these particles are only present in very small quantities, the applied electric field is not necessary to maintain the low viscosity of the suspending fluid. When there is no electric field present, the particles act like fluids; when the electric field is there, the particles behave like solids.

Magnetorheological Fluids

Magnetorheological fluids contain magnetizable particles in an oil that serves as a carrier, such as iron particles in an oil-based carrier fluid, carbonyl iron particles in a silicone oil-based carrier fluid, magnetite particles in a water or glycol-based carrier fluid, and ferrite particles in a silicone oil-based carrier fluid. Magnetorheological fluid may additionally contain a surfactant in order to improve the suspension of the solid magnetized ferrometallic particles. These fluids’ flow properties immediately alter when an electrical current is introduced. As a result, a low viscosity fluid may become viscous by merely introducing an electrically regulated magnetic field. The size of the magnetic field applied directly correlates with the degree of viscosity change.

Applications of Rheological Fluids

These fluids are employed in several systems, including robotics, clutch and brake systems, damping and shock absorber systems, and damping and shock absorber systems. When exposed to an electric or magnetized field, these fluids experience a quick and reversible increase in viscosity and behavioral rigidity. This characteristic enables exact control and modulation of force, vibration, and motion.

Thermoresponsive Materials

Materials that change quickly and irreversibly in reaction to temperature changes in terms of their structure, size, and solubility are known as thermoresponsive materials. These items fall into two groups in specific:

- Thermoresponsive polymers: Some polymer materials change their properties, like solubility, in a reversible way in response to temperature changes. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), poly(acrylic acid), and other thermoresponsive polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymers are examples.

- Thermoresponsive hydrogels: These are hydrogel substances that show a reversible volume phase transition in reaction to temperature changes. The hydrogel alters its volume or swelling behavior at a specific temperature, enabling the controlled release of medications or biomolecules that have been encapsulated. Hydrogels made of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) are two examples of thermoresponsive hydrogels.

Thermoresponsive Materials Applications

- Biomedical engineering: Thermoresponsive polymers are used in drug delivery systems, tissue engineering, and biomaterials. The common use is the controlled release of therapeutics or taking control over biomedical devices’ adhesive and adsorptive behavior.

- Food industry: These polymers are used to create packaging that can maintain a specific temperature or release flavor or color additives in response to temperature changes.

- Microfluidics: These polymers are used in microfluidic devices to control the flow and direction of fluids based on temperature changes.

- Optical devices: Thermoresponsive polymers are used to produce optical devices such as lenses that can change their focal length in response to temperature changes.

- Sensor technology: Thermoresponsive polymers are used in sensor technology to detect temperature changes and other stimuli.

Chromic Materials

Among intelligent materials, a family of materials alters its color in response to varying environmental circumstances. They can switch back to their original color as soon as that impact wears off. The term “chameleon materials” refers to substances that can exhibit this potential since chameleon animals can conceal themselves by changing their skin color. The ability to change color depends on certain physical factors for each family.

Thermochromic

A temperature change causes thermochromic materials to alter their color reversibly. A crystalline phase and structure shift causes a color transformation.

The color former, color developer, and solvent are the main components of thermochromic materials, which are often organic leuco-dye combinations. A cyclic ester serves as the color former and determines the base color. A mild acid called a color developer creates the color shift and ultimate color intensity. The color transition temperature depends on melting point of solvent (alcohol or ester) [12]. This leverage to customize transition temperature depending on the applications. With a transition temperature of 20 to 30 °C, thermochromic materials used in construction applications may improve the thermal roof performances for various seasons. Building materials have integrated thermochromic pigments, such as ordinary white coatings, colorful paints with the addition of TiO2, and white textile membrane coverings. These materials are also widely employed in a variety of fields. For instance, thermo-strips can be used as temperature indicators, particularly for identifying fever.

Photochromic

Photochromics are typically sensitive to visible and ultraviolet light and can change colors depending on the intensity of a particular range of light. Both organic and inorganic compounds include photochromic elements.

It is possible to produce optical switches, optical data storage devices, energy-saving coatings, eye protection spectacles, and privacy barriers using photochromic materials. Photochromic materials and systems have a variety of significant applications depending on the speeds of optical changes. For instance, optical data storage media benefit from very slow transformations, but optical switches need quick transformations.

The principal use of photochromic compounds, such as diarylethene (DE), furylfulgide (FF), and dithienylethene (DT) derivatives, is optical information storage since they are thermally stable and resistant to photochemical side reactions.

In order to develop optical switches, photochromic molecules like spiropyrans (SP) and spirooxazines (SO) have been incorporated into sol-gel glasses. The matrix’s environment has an impact on both the rates of back responses and those caused by light-driven structural changes. Some textile fabrications and protective clothing for the military use photochromic materials [13].

Electrochromic

Transparent or reflective electrochromic materials can be manufactured. These materials’ compositions are electrical voltage-sensitive.

Electrochromic materials can change their color and transparency to solar radiation in a reversible manner when exposed to a weak electric field (1–5 V). Metal oxides of transition are the primary substances exhibiting electrochromic characteristics, particularly WO3, MoO3, IrO2, NiO, and V2O5. There are several uses for the electrochromic effect, such as applying a voltage to reduce the transparency of electrochromic glass.

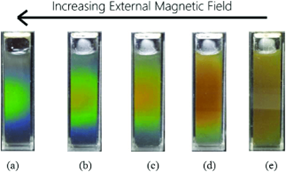

Magnetochromic

Some specific materials, known as magnetochromic materials, can be influenced by magnetic fields to alter color. This material comes in the form of ferrofluids, including magnetic particles between 5 and 10 nm [14]. The particles routinely align when a magnetic field is applied, which causes incident rays to be dispersed from several semi-parallel planes of particles that are suspended. Figure 6 shows a magnetochromic film that has been subjected to various magnetic field strengths.

Figure 6: Fe3O4 nanoparticles fluid color changing phenomenon with increasing magnetic field.

Piezochromic

Piezochromic materials alter certain physical characteristics like absorbability, emissivity, reflectivity, or transparency by applying a certain pressure and using the bathochromic shift. Palladium (Pd) requires more than 1.4 GPa to convert from green to red, whereas CuMoO4 molecules require 2.5kbar [15]. Many piezochromic materials can only change color under extremely high pressure, making them unsuitable for use, especially in color pressure sensors. However, some polymers exhibit bathochromic shifts with only 8 kbar of pressure [16]. Figure 7 shows a schematic representation of a typical piezochromic material whose color changes in response to an external load.

Figure 7: Color changing phenomenon of piezochromic material

pH sensitive Materials

pH sensitive materials are a group of smart materials that can alter color in response to a particular pH fluctuation. They can react with their opposing counterpart whether they are basic or acidic. They have a variety of uses, including enhancing surfaces, acting as filters, and delivering drugs in medicine [17]. One of the best pH indicators utilized in pertinent sensors is halochromic material. They alter their color through a chemical reaction involving hydrogen ions and hydroxides. pH chromic materials are employed in the bandage to aid medical professionals in identifying any changes in burnt patients.

The pH sensitive materials include chitosan, hyaluronic acid, alginic acid and dextran. Typical pH-responsive polymers are poly((meth)acrylic acid), poly(aspartic acid) carboxy groups, poly(glutamic acid), poly[2-(phosphonooxy)ethyl methacrylate], poly(styrenesulfonic acid), etc.

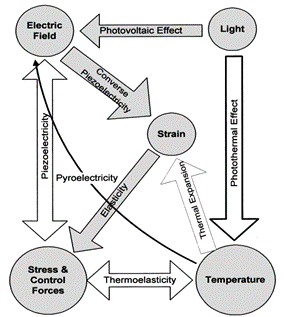

Photostrictive Materials

The photovoltaic and converse piezoelectric effects are two essential opto-electromechanical phenomena that make up the photodeformation process known as photostriction.

When exposed to light, certain materials experience mechanical deformation or strain. The interplay between light and the material’s interior structure produces this characteristic.

Photostrictive materials’ strain or deformation applications include energy harvesting, optical switching, sensing, actuation, and sensing. For instance, light-responsive sensors and actuators that transform light energy into mechanical energy may both be made using photostrictive materials.

Lead magnesium niobate-lead titanate (PMN-PT) shows photostrictive behavior. Certain polymers, ceramics, and metals are additional materials that display photostrictive behavior.

Figure 8: Photodeformation and photostriction characteristics

Photoferroelectric Materials

Materials with both ferroelectric and photoactive characteristics are known as photoferroelectric materials. Ferroelectric materials can permanently change their electric polarization in response to an external electric field. Photoferroelectric materials are desirable for various applications, including photovoltaic devices, photodetectors, and memory devices, due to their combination of ferroelectric and photoactive features. For instance, very effective solar cells that convert sunlight into energy can be built using photoferroelectric materials.

Bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3), lead titanate zirconate (PbTiO3-PbZrO3), and barium titanate (BaTiO3) are a few examples of photoferroelectric materials.

For a long time, photoferroelectric materials like lead lanthanum zirconate titanate have been used to save data in data storage devices. The application of a light signal causes these materials to become somewhat polarized. The ferroelectric domains rotate or reverse in the exposed parts in response to a positive bias voltage while staying stationary in the unexposed sections.

Superconducting Materials

Metallic conductors exhibit electrical resistance at room temperature as a result of impurities, flaws, and ion oscillations within the lattice structure. However, the resistance from the vibrating ions decreases as the temperature of some materials rises. When the temperature falls below a specific level, called the critical temperature (Tc), many alloys, nonmagnetic elements, and other compounds transform into a superconductive state.

Nb3Sn and Nb-Ti are the two most often used engineering superconductors. The necessity to chill them with liquid nitrogen arises because their Tc is only approximately 9 K (-264 C). YBa2Cu3O7-x, often known as YBCO, is the most well-known high-temperature superconductor. It has a Tc above liquid nitrogen (77K) with a Tc of 92K (-181 C).

High-temperature superconductors nevertheless face considerable obstacles in terms of practical uses despite having higher critical temperatures, such as their brittle character, high price, and issues in producing long wires or tapes.

Self-healing Materials

The mechanical characteristics of self-healing materials can be restored following a fracture. Self-healing materials can save ecosystems and resources by extending the lifetime of the materials. Researchers have been interested in self-healing materials for many years because they offer excellent product durability and satisfying material qualities. Self-healing can significantly increase a material’s useful life, and this property has been recognized as a key consideration in the design of sustainable infrastructure.

Self-healing encompasses all kinds of materials, including metals, ceramics, and cementitious materials, even though polymers or elastomers are the most popular self-healing materials. The material can heal itself or requires the addition of a healing agent housed in a microscopic vessel. A substance should undergo the healing process without assistance from outside sources in order for it to be precisely classified as autonomously self-healing. However, self-healing polymers may start healing in response to an outside stimulus (light, temperature change, etc.).

A material that can organically repair wear and tear from regular use might minimize expenses associated with material failure, cut costs associated with numerous different industrial processes due to the extended component lifespan, and lessen inefficiencies brought on by deterioration over time.

Self-healing science and technology have advanced more quickly during the past ten years, developing novel polymers, polymer blends, polymer composites, and intelligent materials with self-healing properties. Numerous damage mechanisms at the molecular and structural levels can now be successfully resolved by incorporating self-healing properties in polymeric materials. Due to their outstanding qualities, self-healing materials find use in various industries, including coatings, electronics, biomedicine, and aerospace. Self-healing materials’ accuracy and design are important for commercial manufacturing in several industries. In addition to the sectors listed above, self-healing concrete, rubber, etc., have drawn much interest from scientists. Many areas are still understudied and offer excellent potential for developing new self-healing polymers that will be attractive for advanced engineering applications.

Conductive Polymers

Conductive polymers are a class of organic materials that have the ability to conduct electricity. The most significant advantage of conductive polymers is their processability, primarily through dispersion. Unlike traditional conductors like metals, conductive polymers comprise long chains of repeating units containing conjugated pi-electron systems. These pi-electrons can delocalize along the length of the polymer chain, allowing for the efficient transport of charge.

Conductive polymers have a variety of unique properties that make them useful for a range of applications, including:

- Flexibility: Conductive polymers can be made into flexible films, making them useful for applications where traditional rigid conductors are unsuitable.

- Easy processing: Conductive polymers can be easily processed into various shapes and sizes using common techniques like inkjet printing, spin-coating, and spray coating.

- Tunable properties: The electrical conductivity of conductive polymers can be tuned by changing the chemical structure of the polymer, allowing for a wide range of conductivities to be achieved.

- Biocompatibility: Some conductive polymers are biocompatible, making them useful for biomedical applications such as biosensors, neural interfaces, and drug delivery.

Examples of conductive polymers include polyaniline, polythiophene, and polyacetylene. These materials are being researched for a variety of applications, including sensors, organic solar cells, organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), and electronic devices.

Endnotes

[1] Braun, E., and MacDonald, S. (1982). Revolution in miniature: The history and impact of semiconductor electronics. Cambridge University Press.

[2] Akiyama, M., Kamohara, T., Ueno, N., Kano, K., Teshigahara, A., Takeuchi, Y., and Kawahara, N. (2010). Piezoelectric thin film, piezoelectric material, and fabrication method of piezoelectric thin film and piezoelectric material, and piezoelectric resonator, actuator element, and physical sensor using piezoelectric thin film. In: Google Patents.

[3] Ward, M. A., and Georgiou, T. K. (2011). Thermoresponsive polymers for biomedical applications. Polymers, 3(3), 1215-1242.

[4] Newnham, R., Sundar, V., Yimnirun, R., Su, J., and Zhang, Q. (1997). Electrostriction: nonlinear electromechanical coupling in solid dielectrics. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 101(48), 10141-10150.

[5] Jaffe, B. (2012). Chapters 5-7 in Piezoelectric Ceramics, Vol. 3. In: Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

[6] Coutte, J., Dubus, B., Debus, J.-C., Granger, C., and Jones, D. (2002). Design, production and testing of PMN–PT electrostrictive transducers. Ultrasonics, 40(1-8), 883-888.

[7] Davoudi, S. (2012). Effect of temperature and thermal cycles on PZT ceramic performance in fuel injector applications

[8] Kaushal, A., Vardhan, A., and Rawat, R. (2016). Intelligent material for modern age: a review. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, 13(3), 10-15.

[9] Dye, D. (2015). Towards practical actuators. Nature materials, 14(8), 760-761.

[10] Stoeckel, D. (1990). Shape memory actuators for automotive applications. Materials & Design, 11(6), 302-307.

[11] Schetky, L. (1984). Shape memory effect alloys for robotic devices. Robotics Age, 6(7), 13-17.

[12] Karlessi, T., Santamouris, M., Apostolakis, K., Synnefa, A., and Livada, I. (2009). Development and testing of thermochromic coatings for buildings and urban structures. Solar Energy, 83(4), 538-551.

[13] Wilusz, E. (2008). Military textiles. Elsevier.

[14] Sung, Y. K., Ahn, B. W., and Kang, T. J. (2012). Magnetic nanofibers with core (Fe3O4 nanoparticle suspension)/sheath (poly ethylene terephthalate) structure fabricated by coaxial electrospinning. Journal of magnetism and magnetic materials, 324(6), 916-922.

[15] Takagi, H. D., Noda, K., Itoh, S., and Iwatsuki, S. (2004). Piezochromism and related phenomena exhibited by palladium complexes. Platinum Metals Review, 48(3), 117-124.

[16] Bamfield, P. (2010). Chromic phenomena: technological applications of colour chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry.

[17] Chaturvedi, K., Ganguly, K., Nadagouda, M. N., and Aminabhavi, T. M. (2013). Polymeric hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. Journal of controlled release, 165(2), 129-138.

To all knowledge

To all knowledge