East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline

1 Background

In 2006, Lake Albert sparked hopes in Uganda when 6.5 billion barrels of oil were discovered in the Albertine Graben, the basin of Lake Albert. Located on the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lake Albert is the northernmost of the chain of lakes in the Albertine Rift.

Oil exploration company Hardman Resources discovered Uganda’s oil at three western fields: Weraga 1, Weraga 2 and Mputa. Out of the 6.5 billion barrels discovered, only 2.2 billion barrels can be extracted. The oil reserves are expected to last up to thirty years, with production peaking at 230,000 barrels a day, so the discovery brought enormous economic hope for one of the poorest countries in the world.

However, Uganda needed a pipeline to transport the oil from the wells to the outside world. Fourteen years after discovering sub-Saharan Africa’s largest oil reserve, a great deal of work has been done in preparation for the construction of the longest heated pipeline in the world. They call it The East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).

2 Location of the Pipeline

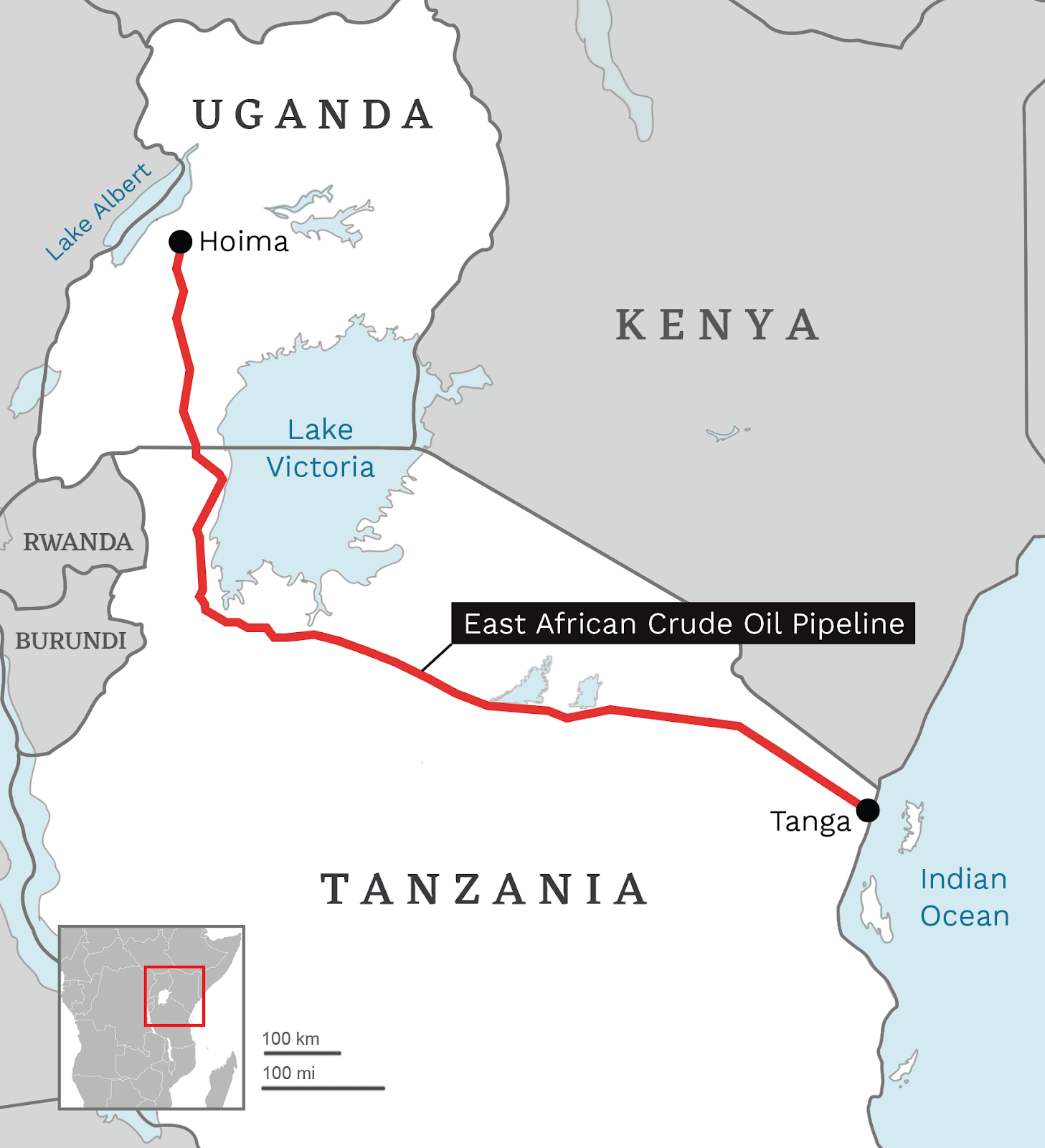

EACOP begins in Buseruka in the Hoima District, 1,120m above sea level in Uganda’s Western Region. It will run for approximately 1,147km from the Uganda-Tanzania border and traverse eight regions and twenty-five districts to terminate at a peninsula north of Tanga in Tanzania. It will travel in a general south-easterly direction, passing through Masaka in Uganda and Bukoba in Tanzania and looping around Lake Victoria’s southern shores.

The Lake Victoria Basin, which 30 million people depend on for their livelihoods, is one of East Africa’s most prominent landmarks. It provides the headwaters of the White Nile and is central to the development and regional integration of the East Africa Community. It is the second-largest freshwater lake in the world.

The Ugandan section of the pipeline will be approximately 296km long, starting near Hoima (close to Lake Albert) and traversing ten districts and 25 sub-counties to the Tanzanian border between Masaka and Bukoba. The Tanzanian section will comprise approximately 80% of the pipeline’s total route length. The oil pipeline reaches a maximum elevation of 1,738m above sea level along the Tanzanian route portion when crossing the East Africa Rift zone. The pipeline continues through Shinyanga and Singida town and terminates at the Port of Tanga—the most northern port city of Tanzania—west of the Indian Ocean.

https://www.irinsider.org/environment-1/2021/3/6/east-african-oil-pipeline-sparks-disputes-between-banks-and-ngos

3 Technical Description

3.1 GENERAL STRUCTURE

The 1,444km-long EACOP system, consisting of a 24-inch-wide carbon steel pipeline, will be buried to a depth of up to 2 meters along most of its route. The oil from the Lake Albert basin has a very high viscosity. The entire pipeline will be thermally insulated with polyurethane foam (PUF), and electrical heat tracing (EHT) will be installed. The heating system consists of EHT cables. It is powered through a buried high voltage cable (33kV) that feeds EHT substations and mainline valve sites along the route to maintain a minimum temperature of 50° Celsius. The heat ensures the wax remains a solution. The EHT cables (6.6kV) provide up to 30W/m of heat. The pipeline will be insulated with 70mm of polyurethane foam (PUF) material for heat retention.

For preventive purposes, the pipeline is specified with a fusion-bonded epoxy anti-corrosion coating applied to protect the pipe throughout its operational life against external corrosion. This fusion-bonded epoxy coating will act as a second barrier in water ingress below the bonded thermal insulation system.

3.2 PUMP STATIONS

The pipeline will be buried at a depth of between 1.8–2 meters along most of its length, though it will be buried deeper at river and road crossings. The only elements of the pipeline infrastructure visible are the pumping stations, electrical heat tracing stations, block valve stations, marine storage terminals (MST) and loading facilities.

While the product begins its journey with natural pressure, it loses momentum over time and distance due to friction losses. Pumping stations are positioned throughout the pipeline’s length to intermittently boost the pressure, pump the product along the line, and monitor the flow and other relevant information about the crude transfer. EACOP will have a total of six pumping stations and two pressure reduction stations.

Uganda’s 296km pipeline section consists of two pumping stations to keep the oil moving. It also has nineteen valves at critical locations where the oil flow can be reduced or stopped and electrical substations collocated to power the electrically heated cable.

Tanzania’s 1,149km pipeline section consists of four pump stations, two pressure reduction stations (PRS), fifteen prefabricated electrical heat tracing (EHT) substations, and an integrated SCADA/ICS system using fiber-optic cabling and telecommunications with redundant control functions at Tilenga and a marine storage terminal.

Pump station locations are determined by pipeline hydraulics, taking into account factors such as pipe size, topography, frictional losses related to oil flow, and the location of other pumps in the system. The selection of pump station locations also considers proximity to roads and power lines, land use, and environmental characteristics.

Pump Station #3 is approximately 105km from the Border of Uganda. Pump Station #4 is 205km from Pump Station #3 (PS3) and 214km from Pump Station #5 (PS5). Hydraulic spacing is due to a gradual elevation descent of 143m over the 419km distance. The elevation of PS5 is the lowest of all four stations, with an elevation ascent of 454m before reaching Pump Station #6. The permanent access road of approximately 800m is also the shortest of all of Tanzania’s facilities. Each pump station is self-contained with its power generation.

Each pump station will require a total area of 310 × 400m plus a 50 × 50m helipad. Each pump station will establish security facilities and an emergency evacuation area outside the pump station fence. The emergency pipeline repair system (EPRS) will most likely be at PS3 and PS5 and the marine storage terminal (MST), or close to existing industrial activities near the EACOP route.

4 Completion

Final project investment decisions are expected to be issued by partners by December 2020. Construction of the project infrastructure is expected to begin in early 2021. Other pending agreements include the Shareholders’ Agreement (SHA), Ports Agreement (PA), and Land Lease Agreement (LLA). Following the global pandemic, the Ugandan government has officially announced that the final investment decision for the EACOP project will be signed off during the first quarter of 2021 to 21 November 2021.

5 Participants

In April 2020, Tullow Oil Plc sold its interests in Uganda’s Lake Albert development project—including the East African Crude Oil Pipeline—to Total SA, for US$575 million. As of April 2020, the owners of the EACOP are Total SA (with 45%), Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) (15%), China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) (15%), and Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) (5%).

6 Financing

The EACOP project is estimated to cost $3.5 billion and is built to transport crude oil from Uganda’s oil fields in Hoima to the Tanzanian port of Tanga. The 1,444km planned pipeline is expected to be built at a budgeted cost of US$3.5 billion. 30% of the project costs are expected to be provided by the equity investors in the project, with the remaining US$2.5 billion to be provided via project finance loans.

Negotiations and the search for international lenders are ongoing. The Standard Bank of South Africa is advising Uganda and Tanzania, while Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation is advising Total SA. The London-based law firm Clifford Chance is advising Total SA on legal matters, while the Industrial and Commercial Bank advises CNOOC of China. The Standard Bank of South Africa and Sumitomo Mitsui are also acting as joint lead arrangers for the project loan.

The Sumed Pipeline

1 Background

After Egypt closed the Suez Canal during the Six-Day War, for precisely eight years from June 1967–1975, the project for an alternative route and oil pipeline from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean commenced. The establishment of SUMED (also known as the Suez-Mediterranean Pipeline) pipeline company was agreed upon in 1973 between five Arab governments.

By linking the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, the cross-border pipeline allows Gulf nations to deliver oil to European markets. The pipeline would act as an essential alternative delivery system that bypasses and complements tankers used in the Suez Canal. It is a substantial revenue earner for the Egyptian government.

2 Location

The SUMED Pipeline is a crude oil pipeline located in Egypt. It competes with the Suez Canal by transporting crude oil from large tankers that can’t pass fully-laden through the Suez Canal. It runs from the Ain Sokhna terminal in the Gulf of Suez, near the Red Sea, to offshore Sidi Kerir, Alexandria in the Mediterranean Sea. By linking the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, the SUMED is a cross-border pipeline and an alternative to the Suez Canal that allows the Gulf nations to deliver oil to European markets.

3 Technical Description

The SUMED pipeline is 320 kilometres (200 miles) long and is made up of two parallel pipes of 42 inches (106.68cm) in diameter. It links the Ain Sukhna terminal on the Gulf of Suez to the terminal at Sidi Kerir and can transport different grades of crude oil with minimal contamination.

The pipeline has a capacity of 2.5 million barrels of oil a day and pumped a record 113 million tons in 2006. It can accommodate both very small tankers and those over 500,000 tons. Many tankers too large to use the Suez Canal can unload a portion of their oil in Ayn Sukhna, sail through the canal, and reload in Sidi Krayr.

The vast majority of crude entering the SUMED pipeline comes from Saudi Arabia, with Kuwait and Iraq contributing much less. Almost 80% of the oil shipped from the Arabian Gulf to Europe passes through the SUMED pipelines.

4 Completion

The establishment of the pipeline company was agreed upon in 1973 between five Arab governments. The consortium opened the pipeline in 1977.

5 Participants

The pipeline is majority-owned by Egypt’s state oil company, the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC). Saudi Aramco, the Kuwait Investment Authority, and Qatar Petroleum have smaller shares. Ownership breakdown is as follows: EGPC (50%, Egypt), Saudi Aramco (15%, Saudi Arabia), International Petroleum Investment Company (15%, the United Arab Emirates), three Kuwaiti companies (each with 5%), and Qatar General Petroleum Corporation (5%, Qatar).

6 Financing

The SUMED pipeline was financed by a consortium of Arab countries: primarily, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Egypt.

Nembe Creek Pipeline

1 Background

Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil producer and ranked as the 11th-largest oil producer in the world; a top crude oil supplier for the US. The Nembe Creek Trunkline (NCTL) was constructed in the Niger Delta by the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC) as a replacement for the ageing Nembe Creek Pipeline suffered significant losses due to ongoing fires, sabotage, and theft. NCTL is one of Nigeria’s major oil transportation arteries that evacuate crude from the Niger Delta to the Atlantic coast. The project replaced more than 1000 km of deteriorated major pipelines and flowlines.

2 Location

OML 29 is a large block located in the southeast Niger Delta. It contains 11 oil and gas fields, the largest of which is Nembe Creek. The pipeline runs from the Nembe Creek oil field in the Niger Delta to the Bonny export Oil Terminal, located in Rivers State. Crude is exported by the NCTL, which runs 97 kilometers east from Nembe Creek to the manifold at the Cawthorne Channel field on OML 18. From here, crude is evacuated the short distance to the Bonny oil terminal.

3 Technical Description

NCTL is a 97-kilometre pipeline that involves three sectional pipelines: 5km of 12-inch-diameter pipeline from the Nembe Creek III manifold to the Nembe Creek tie-in manifold; 44 km of 24-inch-diameter pipeline from Nembe Creek to San Bartholomew; and 46 km of 30-inch-diameter pipeline from San Bartholomew to Cawthorne Channel. The transportation capacity is 150,000 b/d at Nembe Creek, however, up to 600,000 b/d of liquids can be evacuated from the endpoint at Cawthorne Channel, moving oil from a total of 14 oil-pumping stations.

4 Completion

The construction of the NCTL started in 2006 and was commissioned in 2010 at the cost of $1.1 billion.

5 Participants

NCTL was constructed by Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) in a joint venture comprised of Total E&P Nigeria Limited and Nigerian Agip Oil Company Limited. Aiteo Group owns the NCTL, which recently purchased it from SPDC as part of the related facilities of the prolific oil block OML 29. By March 2015, the SPDC—a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell plc (Shell)—completed its interest in OML 29 and the Nembe Creek Trunk Line to Aiteo Eastern E&P Company Limited, a subsidiary of Aiteo Group. The other joint venture partners, Total E&P Nigeria Limited and Nigerian Agip Oil Company Limited, also assigned their interests of 10% and 5% (respectively) in the lease, ultimately giving Aiteo Eastern E&P Company Limited a 45% interest in OML 29 and the Nembe Creek Trunk Line.

6 Operations

In 2012, Shell estimated that 140,000 barrels of crude oil, valued at $16 million, was being stolen daily. In December 2011, barely one year after the line was commissioned, the pipeline was shut down for one month to repair leaks caused by crude thieves. On 2nd May 2012, NCTL shut down the NCTL pipeline due to constant crude theft activities, and on 4th May 2012, SPDC declared a force majeure on outstanding cargoes of Bonny Light.

Tazama Pipeline

1 Background

In 1965, more than 90% of Zambia’s oil import were routed through Rhodesia. In November 1965, Rhodesia had a Unilateral Declaration of Independence which forced Zambia to import all of its petroleum products by road tankers through the port of Dar es Salaam. Zambia airlifted supplies until October 1966, by which time, a less costly and more independent road transport organization was operative—Tanzania Road Services Ltd. was formed in June 1966. Still, the roads were not capable of carrying the traffic, and many people lost their lives. A pipeline was needed.

In January 1967, the Tanzanian and Zambian government negotiated a pipeline convention to regulate the pipeline’s construction, operation, and maintenance. They also sought control of such matters as tax status, wayleave easements and ownership, shareholding, market share, and other rights and privileges. The two governments constructed the TAZAMA Crude Oil Pipeline due to Zimbabwe’s unilateral declaration of independence and the British policy of economic sanctions against Zimbabwe. (TAZAMA stands for Tanzania Zambia Mafuta and “Mafuta” means “Oil” in Kiswahili.)

2 Location

The TAZAMA Pipeline (also called Tanzania–Zambia Crude Oil Pipeline), runs from the Single Point Mooring terminal at Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to the Tanzanian and Italian Petroleum Refining Company (TIPER) refinery in Dar es Salaam and then to the Indeni refinery in Ndola, Zambia. The pipeline passes through or near the following parks, cities and towns: Dar es Salaam, Morogoro (which hosts the Mikumi National Park, Elephant pass), Iringa, Mbeya, Chinsali, Kalonje, and Ndola.

3 Technical Description

3.1 GENERAL STRUCTURE

TAZAMA is the longest pipeline in Africa, requiring 45,000 tons of steel pipe after being imported from Italy via the Cape. The pipeline travels approximately 1,710 kilometres (160 miles) from the Single Point Mooring terminal at Dar es Salaam to the Indeni refinery Ndola Zambia. For 954 kilometres (593 miles), the pipeline has a diameter of 8 inches (20cm); for the remaining 798 kilometres (496 miles), the pipeline diameter is 12 inches (30cm). The flow rate of the crude oil is 230 km/h (1.8 Mlcm/year).

3.2 SINGLE POINT MOORING FACILITY (SPM)

Once offloaded from the tanker, the crude oil starts its journey via the Single Point Mooring Facility pipeline on the Indian Ocean. The oil tankers dock at the Single Point Mooring (SPM) facility, about 7km from the TAZAMA Tank Farm. At the SPM, Crude oil is pumped from the ship using flexible pipes, which lie on the sea bed, extending 3km from the shoreline. The crude then flows into the storage tanks at the TAZAMA Tank Farm.

3.3 TAZAMA TANK FARM

The TAZAMA Tank farm is a storage facility for the crude pumped from ships. It has six storage tanks, each with a capacity of 35,000m3 and a combined total of 210,000m3. The Tank farm also has a pump station, which pumps the crude through the pipeline. Each pump station gives the crude oil enough pressure to flow to the next pump.

3.4 PUMP STATIONS

The Morogoro Pump Station is about 200km from Dar es Salaam. There is a total of 7 pump stations along the pipeline from Dar es Salaam to Ndola. Due to the hilly terrain in Tanzania, there are 5 pump stations to push the crude through the pipeline, which, in one instance, is at an almost vertical angle. In southern Tanzania, the terrain is rugged with many rivers and the two arms of the rift valley system to be crossed. From Dar es Salaam, the pipeline climbs to almost 7000 feet in southern Tanzania before following the comparatively easy watershed route through northern Zambia to Bwana Mkubwa at 4200 feet above sea level. There are two pump stations in Zambia, which has a relatively level terrain. All seven pump stations use reciprocating engines which run on crude oil.

4 Completion

In 1968, TAZAMA Pipelines Limited was incorporated. The pipeline was commissioned in 1969. In 1991, there was a repair and part-replacement of the existing 8″ diameter and 12″ diameter pipelines. The World Bank supported the project. The same engines that were installed 40 years ago are still in operation at the pumping stations.

4.1 POTENTIAL UPGRADE

As of November 2016, both the Tanzanian and Zambian governments have discussed either modernising the ageing TAZAMA pipeline or creating a new pipeline to run parallel to the original. The new project aims to facilitate the transportation of crude oil, refined oil, and natural gas.

In May 2020, TAZAMA Pipeline said that it was seeking a $400 million loan to expand the 954-km, 8-inch portion of the pipeline to the total 12-inch diameter of the remainder of the pipeline. With the loan, Sunyama, TAZAMA’s Tanzania Regional Manager, says that the company will be able to upgrade the entire pipeline to 12 inches. The current pipeline’s diameter limits its pumping capacity to 2 million litres a day, while the upgrade would drastically increase the capacity to approximately 1.1 billion litres a day.

5 Participants

The pipeline is owned and operated by TAZAMA Pipeline Limited—a joint company of the governments of Zambia (66.7%) and Tanzania (33.3%)—with headquarters in Ndola Zambia and an office in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

6 Financing

The TAZAMA pipeline was funded by Mediobanca, a consortium of Italian banks. The term is 6%, repayable in 15 equal annual instalments beginning one year after the pipeline became operative. Early in 1967, separate agreements were signed between the governments of Italy and Tanzania and Italy and Zambia to provide Italy with credit of 5,542,407 and 11,070,00 GBP respectively, for pipeline construction. Repayments of the loan will be made from the current earning of the pipeline despite estimated running costs of 400,000 a year.

Chad-Cameroon Pipeline

1 Background

Oil exploration began in Chad in 1969. Several oil discoveries were made in both the Lake Chad Basin and the Doba Basin in southern Chad by a consortium comprising Chevron, Conoco, ExxonMobil and Shell in the 1970s. However, Chad’s oil industry never had much chance of getting off the ground due to civil war and political instability from 1965 until the early 1990s. With the return of peace to the country in the early 1990s, the rising price of oil and the United States of America’s increasing interest in diversifying its sources of oil led to renewed interest in Chad as an oil-producing country and a serious player in the petroleum industry.

In 1996, ExxonMobil discovered between 800 million and 1 billion barrels of oil in the Doba basin. This finding set into motion what would become the Chad-Cameroon Pipeline and Project Development, one of Africa’s most significant private sector investments. The project was developed by a Consortium of ExxonMobil (USA), Chevron (USA), and Petronas (Malaysia), with ExxonMobil (also known as Esso Exploration and Production Chad Incorporated, EEPCI or Esso) as the operator.

Today, Chad is the 11th biggest oil-producing country in Africa and the 48th largest oil-producing country globally.

2 Location of the Pipeline

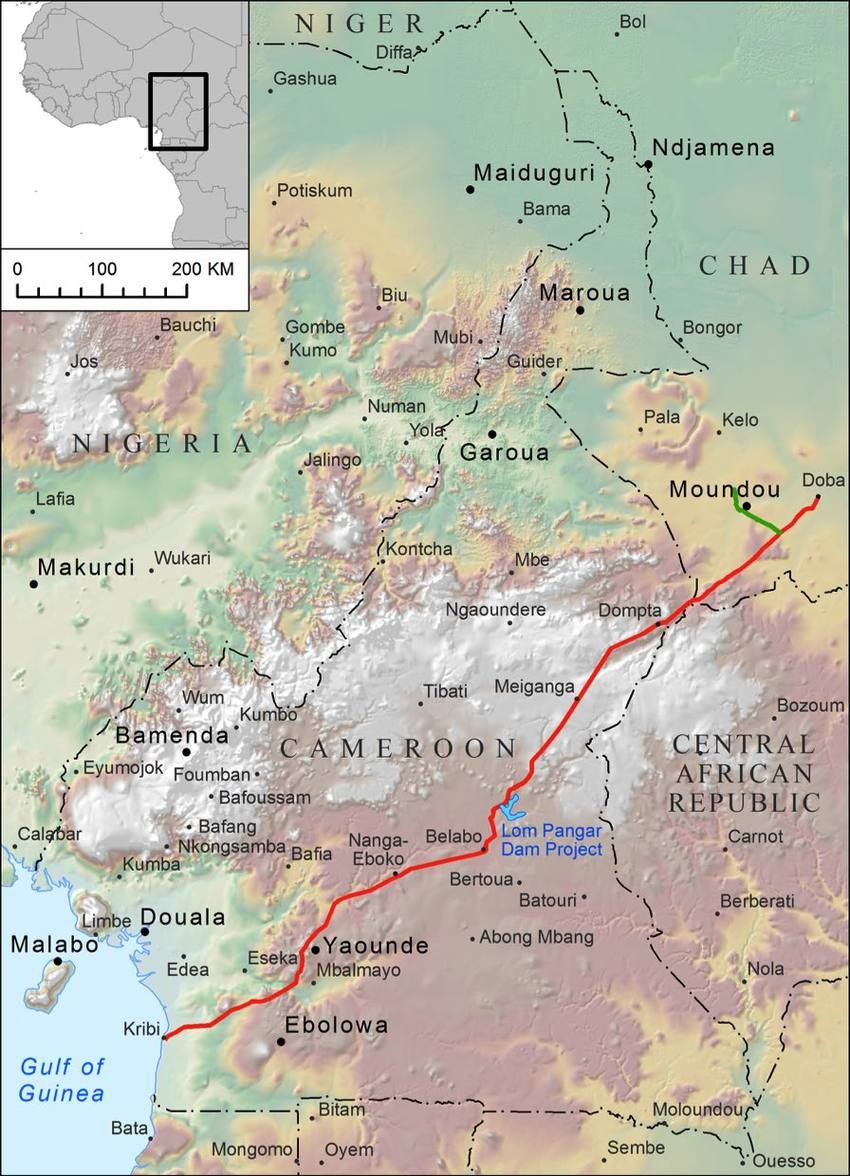

Chad is located in Central Africa and without direct access to the sea. It requires a pipeline to bring its oil to the world. The Chad–Cameroon Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project is near Doba in southern Chad. The project consisted of developing three oil fields (Komé, Bolobo and Miandoum) in the Doba region with a buried pipeline to link them.

In the savanna of southern Chad, an intricate maze of pipes, tanks, and processing equipment at the Central Treatment Facility turns frothy emulsion from 300 oil wells into valuable pure crude oil. The Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline transports the crude oil from southern Chad through a tropical forest to Kribi, Cameroon’s Atlantic coast. From there, the oil is shipped to floating storage and offloading vessels, 11 km (7 miles) offshore for export, ready for sale in global markets.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-Chad-Cameroon-Oil-Pipeline_fig4_317551747

3 Technical Description of the Pipeline

The Chad-Cameroon pipeline is a 1070-kilometre-long, 30-inch-wide buried pipeline. There is no refinery for the Doba crude to be sent to, so the oil goes straight into the pipeline and directly onto supertankers parked off the Cameroonian coast.

In Chad, there are three oil fields near Doba (called Komé, Miandoum, and Bolobo), two collecting stations, and one pumping station. The Central Treatment centre (Komé) can produce up to 225,000 barrels per day of crude. In Cameroon (Dompta, Belabo), there are two pumping stations, a pressure reduction station (Kribi), and offshore floating storage, reaching 12km. The three fields (Komé, Bolobo and Miandoum) were expected to yield an average of 225,000 barrels per day (BPD) but, over an operation period of 25–30 years, Crude Oil recovery is approximately 1 billion barrels.

4 Completion

The pipeline project was initiated in 1976 but took 27 years from concept to completion. Chad was in desperate need to exploit its profitable natural resources, and quickly. The World Bank approved the project on 6th June 2000. On 26th October 2000, the Chad-Cameroon pipeline project was launched. It was completed in June 2003, one year ahead of schedule. The pipeline achieved its first oil in July 2003.

5 Participants

The Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project was an agreement between the Chad and Cameroon government, a consortium of oil companies, and the World Bank.

The original consortium of oil companies involved was Exxon, Royal Dutch Shell, Elf Aquitaine. In 1999, Shell and French oil company Total (then known as Elf Aquitaine) withdrew from Chad due to civil unrest,

In April 2000, Petronas of Malaysia and Chevron acquired stakes in the project. Exxon then enlisted the support of the World Bank to raise support within the international community. The World Bank agreed on the condition that specific environmental and social standards were enforced both in Chad and Cameroon and that the revenues be put towards improving social and economic conditions.

In 2000, a new oil consortium emerged—including Exxon (operating in Chad as Esso), Chevron, and Petronas—and formed the Tchad Oil Transportation Company. The Consortium was American-led, with Exxon and Chevron combined holding 65% of the stake in the deal. The consortium promised an investment of $3.7 billion to drill Chad’s oil. The World Bank’s support was significant for the consortium of oil companies and they believed that they needed the World Bank’s support for the project to succeed.

6 Financing

The total cost of the project was estimated at US$3.72 billion, with the costs of the export system accounting for US$2.2 billion. While the private project sponsors, the Upstream Consortium, provided about 95% ($2.2 billion) of the financing for the pipeline, the World Bank also contributed through debt financing. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) provided a loan of about $100 million, $85.8 million of which went to the Cameroon Oil Transportation Company (COTCO) and $14.2 million to the Tchad Oil Transportation Company (TOTCO). They also helped to secure an additional $300 million in private commercial lending.

7 Controversies

The Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Development and Pipeline Project was opposed by over 80 environmental and human rights groups during its construction due to political, economic, social, and environmental concerns, yet it was also hailed as the best method for reducing poverty in Chad.

To all knowledge

To all knowledge