1 Introduction

1.1 Companies and Society

Social responsibility is about identifying and managing business impacts, both positive and negative, on people. The quality of an organisation’s relationships and commitment to its stakeholders is critical. For instance, extractive companies affect what happens to employees, workers in the value chain, customers, local communities, and minorities, and it becomes imperative to manage impacts proactively.

From the encounter between companies and local communities, social responsibility emerges as something mediated and contested amongst the business and its stakeholders. In these encounters, two preeminent matters are intersecting: a company’s ambition of profit, and the local community’s desire for prosperity, human development, and governance over its own resources. Simultaneously, there exist two main concessions: the company has a need for credibility and recognition in the culture in which it works (licence to operate), and the community has a need for further private economic projects and support. This complex relation leads us to an important question: does an extractive corporation behave in the same manner when it moves into another social order?

To support their commitment to ethical behaviour, multinational firms usually claim that they implement the same rules in every location. However, they behave differently in practice, as “the same institutions work differently in different circumstances, particularly in the absence or presence of open access” [1]. So how do extractive industries adapt their behaviour to their institutional environment? Concerning the international social order, a mix of national and international regulations governs industries’ operations (including between its headquarters and subsidiaries, or with other partners). These regulations stem from central banks, regional organisations like the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) or the European Union (EU), or international organisations like the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The following table specifies four cases (a, b, c and d) depending on the home and host social orders.

Figure 1. Source: Figure 1. Source: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-10816-8

1.2 The Predatory Potential of Extractives

Some natural resources, such as wood, oil, or minerals, can foster social tensions. The clear majority of companies handling these products also display significant economic power. When economic power is important, it is likely to build strong impersonal and personalised relationships with its home social order. This section will analyse some determinants that will foster predatory tendencies; whilst a part of these factors are intrinsic, others are related to its home social order. This section will present some predatory behaviour commonly observed in extractive activities.

An actor’s predatory capacity refers to his propensity to develop predatory behaviours; that is, to move and settle in another social order through the existence of business opportunities, the ability to mobilise resources for this development, and incentives offered by the host social order [2]. From an institutional perspective, a corporation in the extractive industry based only in its own country is mainly subject to national regulation. Once settled in an additional political territory, it is subject to three regulatory systems: (i) its home social order; (ii) the host social order; and (iii) the international social order, which is an international order of predation as revealed above.

Some products and services have destructive attributes due to the production process, or their use generates high social costs. One of the most obvious predatory characteristics is pollution. Such products include hydrocarbons, heavy metals, phytosanitary products, etc. Other are less obvious as they affect lifestyles and institutions within a host social order. Some examples of predatory behaviours are detailed below:

- Corruption of government officials;

- Tax avoidance;

- Intimidation or violence against local stakeholders;

- Use of production techniques, processes, or raw materials that are obsolete or prohibited in their home social orders.

- Waste discharges without treatment, or natural environment destruction without repair;

- Development of transactions with co-contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, or customers who maintain predatory behaviours in their own value chains.

- Complicity in destabilising institutions of host social orders, through fueling of militias or coups.

- Large philanthropic actions as a corruptive approach to divert attention.

- More broadly, the violation or complicity of violation of human rights in the company’s sphere of influence.

Finally, as infrastructure and exploration investments required for oil, gas and mining ventures are substantial, they often mean that exploitation of natural resources in developing countries cannot carry on without the foreign enterprises taking part. For many emergent nations, multinationals’ extractive operations are a vital source of revenue, giving the local authorities a vested interest in protecting those operations against protesters, uncooperative landholders, bandits, or insurgents.

2 The ABCs of Social Responsibility

2.1 Corporate Social Responsibility

Social responsibility aims to identify and manage business impacts on the people either positively or neutrally [3]. Company engagement with stakeholders is a critical aspect of socially responsible business practices. Extractive industries need to manage their business impact proactively, including employees, workers in the supply chain, customers, and local communities. Extractive activities’ social license to operate largely depends on their efforts towards social sustainability. From an emphasis on the natural environment, the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiative has gradually extended its attention to all dimensions of human and social life. Today, CSR discusses human rights abuses in general and fights predation, aiming to transform predatory practices into responsible behaviours.

Figure 1. Corporate social responsibility embraces dual objectives—pursuing benefits for the business and society. Source: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/making-the-most-of-corporate-social-responsibility

CSR is a concept that means different things to different specialists. In a nutshell, it acknowledges that corporations have a range of obligations that consumers, society, law and other stakeholders have entrusted to them. Even though companies’ primary target is to maximise the returns to investors, it has been recognised that their acts impact individuals and local institutions well beyond their transactions. They are therefore supposed to share their returns with society.

As consumers, workforces, and suppliers place increasing importance on CSR, some leaders have begun to look at it as an innovative opportunity to improve their companies while contributing to society radically. They view CSR as fundamental to their overall strategies, helping them to address critical business issues ingeniously. Cultivating an approach that can truly deliver on these lofty ambitions is a big challenge for executives. Some creative businesses have managed to overcome this contest, with intelligent collaboration emerging as one way of simultaneously creating value for both business and society. Smart partnering centres on critical areas of impact between society and business and develops original solutions that draw on both to address main challenges that affect each partner.

2.2 Different Approaches

We can find (at least) four modes of social responsibility and benefit sharing approaches [4]. This classification divides all strategies into paternalistic, company centred social responsibility (CCSR), partnership, and shareholder modes. While we present these “ideal” forms and include their formalised explanations using real examples, it should be noted that in reality, we see a mix of several modes.

Paternalistic mode

In this mode, the state generally dominates: it determines, controls, and intervenes in the policies and practices of companies. In Russia, for instance, it represents both sides of stakeholders: a regional government and a state-run company. The company either (partially) takes the state’s role or contributes significantly to some elements of state support to local populations and Indigenous peoples. The latter parties have a minimal capability of controlling the nature, forms, and delivery of aids. In Russia, this style is rooted in the Soviet legacy and often results in the Native people’s dependency on energy companies, which can be exemplified with the oil industry in the Nenets Autonomous District [5] or the North Slope Borough of Alaska.

A significant flaw of social policies based on the paternalistic model is their inability to ensure residents’ satisfaction. Public policies are typically associated with relatively weak municipal institutions that do not provide fertile community development conditions. Under paternalistic mode, both technical and distributional equities generally are low.

Company centred social responsibility (CCSR) mode

This mode refers to a “narrowly defined” corporate social responsibility approach where an extractive company plays a central role in setting social benefits arrangements by adopting internationally developed standards or standards imposed by various funding agencies or legislation. Recurrently, the CCSR-based schemes are intended to satisfy investors and shareholders while meeting local communities’ needs only to the degree possible for earning the ‘social license’ to operate.

This is the case of a Norwegian shipping company operating in Indonesia as a provider of maritime Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) transportation and regasification services [6]. They realise that their engagement is short-termed, and therefore, they stay away from deep interaction with the local community. They would instead save adherence to government requirements while trying to avoid entering into encounters with locals. Since they have no long term interest in the area where they do seismic operations, the only strategic factor is compensation to the fishermen (required by law) for removing their equipment during seismic mapping.

Figure 3. Tribal members pay tribute to whaling crews in the town of Nuiqsut, the heart of Alaska’s North Slope. Source: https://nativeamericatoday.com/wendy-red-star-gets-the-last-laugh/

Partnership mode

This type of social approach builds tripartite partnerships among the extractive companies, government, and civil society. In theory, this model is better positioned for promoting development and autonomy in the communities. Although partnerships lead to more desirable participation processes and benefit sharing outcomes, they are not devoid of considerable problems, such as internal tensions among beneficiaries.

Such partnerships have been a characteristic of oil extraction on Russia’s Sakhalin Island. Exxon Neftegaz Limited and other operators in the area developed partnerships with the regional state and Indigenous peoples through multilateral agreements, which set up procedures for distributing funds to traditional organisations and family enterprises.

Shareholder mode

Shareholder mode consists of dividend funds as shares from village corporations. Despite rising tensions, it is important to acknowledge that income from oil extraction is shared between companies and host communities, and minorities have broadened economic development opportunities. The shareholder mode may not improve distributional equity but does lead to elevated procedural equity [4].

There are multiple “layers” of social benefits under the shareholder mode in certain spots of the North Slope of Alaska. The Indigenous people are shareholders of the for-profit Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ARSC), for example. ASRC establishes bonds with many oil companies and receives royalties from oil extraction on Native-owned land. Community associations own the land’s surface title, obtain royalties through surface-use agreements, and contract oil field services from foreign companies.

2.3 Oil and Gas

Oil and gas — especially midstream — have faced social pressures earlier, but these pressures have intensified in recent times. Although larger O&G players have sophisticated practices in these areas, governance issues are back in the spotlight since many smaller businesses have joined the shale and unconventional oil sector in the past decade, mainly in North America.

Investors and consumers are pressuring companies to incorporate social responsibility practices into their culture and operations. Social responsibility has gone from a nice-to-have feature to a must-have prerequisite as it encourages investments and will be, in the long run, a deciding factor in winners and losers in the market. The pressure of social responsibility is perceived throughout the oil and gas value chain, with upstream facing most environmental controls and midstream being placed under the microscope for its social impact and governance structure.

For example, building new pipelines in socially sensitive areas, such as those owned by indigenous people, is challenging. Local and international pushback has been a wakeup call to many midstream operators who often checked compliance boxes but did not seek to recognise their projects’ social consequences. Interest in small-scale LNG plants is growing because of escalating public opposition to new pipelines in some regions, such as the US Northeast. Obtaining approval for extra peak shaving capacity has become simpler than building new pipelines [7].

2.4 Mining

Global advances in normative have had a profound effect on major mining companies. By the mid-2000s, sustainable development had been accepted as a normative structure for their CSR policies and practices [8]. However, there is significant variation between firms in terms of the timing, degree of commitment, and the willingness to assume a leadership role in promoting global standards for the mining industry. However, there is a considerable difference between companies in terms of the timing, degree of commitment, and the readiness to assume a leadership role.

More recently, mining to supply electrification, digitalisation, and renewable energy technologies occurs in many countries, but a reduced number of them dominate production. China, Chile, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa and Russia have large production shares for metals used in lithium-ion batteries, rare earth metals, and other metals used in solar PV and wind technologies [9]. Although poorly documented, there have been ongoing negative social, environmental impacts in China, which produces 85-90% of the worlds’ supply.

Like the ones mentioned, countries with existing mining are more likely to have the social licence to operate. However, this does not always mean that they have the principal reserves or resources available. Otherwise, countries with large reserves of several metals for which they only mine small volumes — e.g. Australia, Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia —have the potential to be long term sources alongside existing producers. Many other considerations will affect where mining expands, or new mining takes place, including social and environmental factors.

If managed inappropriately, there are significant social impacts associated with the mining and processing of metals used for renewable energy and clean technologies. These include pollution of water and agricultural soils through the release of wastewater and the triggering of erosion processes, the risk of tailings dam catastrophes, and health impacts from workers and neighbouring communities. But mining can also bring positive economic benefits; nickel mining, for example, is New Caledonia’s largest employer and makes a significant contribution to the GDP of the country.

The transition to a high-penetration renewable energy (RE) system is urgently needed to meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement and increase the chance of keeping global temperature rise below 2 degrees. Recent investment in new RE infrastructure globally has been double that of fossil fuels and nuclear. These technologies, together with electric vehicles and battery storage, require high volumes of environmentally sensitive materials. To avoid creating new adverse social and environmental impacts, the supply chains for these products and technologies need to be adequately controlled.

A wider RE contribution may lead to fewer impacts from coal mining, which is responsible for the greatest number of fatalities and health issues worldwide. With the growing demand for metals from the scaleup in RE, responsible mining practices are necessary to avoid harmful environmental impacts, ensure the respect of human rights, and guarantee an equitable allocation of benefits.

3 Case Studies

3.1 The Incident with Anvil Mining Ltd.

Many extractive operations are established in areas of serious political instability or even conflict zones, assuming that the option of moving to a safer location is simply not available when the intended resources remain firmly in the ground. In reality, lucrative extractive industries will intensify situations of conflict, as opposing factions seek to regulate rents from the operation to finance their own struggles.

In October 2004 Anvil Mining Ltd provided transportation and other logistical support to the Democratic Republic of Congo’s armed forces while they were fighting an armed insurgency in the town of Kilwa. During the conflict, the armed forces committed severe human rights violations against the local civilian population, including summary execution, torture, and rape [10]. Later, some army and Anvil personnel were prosecuted and acquitted in the DCR, with subsequent class actions being aborted in Australia (the company’s home country) and Canada (where its headquarters are located). All cases were dismissed in favour of Anvil Mining, except for a complaint before the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, which ordered the DRC to “prosecute and punish” the company.

Beyond the “hard law” pathways, both civil and criminal, two “soft law” options have also been appealed for seeking accountability for the human rights abuses in the Kilwa incident. Responsibility procedures of the OECD Guidelines and the World Bank’s Compliance Advisor were both pursued following pressure from several civil society groups. This was an attempt to understand the damage caused to the victims of Kilwa and seek some remedy beyond the civil and criminal legal process.

It is undeniable that the Congolese military’s atrocities in Kilwa could not have been carried out in the manner that they were without the assistance delivered by Anvil, even if that assistance was willingly provided or commandeered by the military. The reports from the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) and some non-government organisations implicitly suggest that Anvil may have had some prior knowledge of the imminent military operation or volunteered to support a military reaction to the revolt [11].

This case study should sound a warning over the disjointed nature of state-based regulation of transnational commerce. Despite the possibility for multiple national and international bodies to assert jurisdiction over such an event, the fact remains that political and corporate will to account for responsibilities is at least as necessary as the legal capacity to claim that jurisdiction.

3.2 Oil Exploitation in Nigeria

In Nigeria’s history, oil exploitation impacts have affected the natural environment and the social network. The first oil well was discovered in 1956 in the Niger Delta and was put into operation in 1958 by Shell-BP. Since then, oil activity has generated exceptional revenues in the country, to the point of representing more than two-thirds of the state budget on average over the past decade. It has also generated high costs of an environmental, social, economic or political nature, making Nigeria a fascinating school case illustrating the struggle to address the negative impacts of business activities on society.

At first, the circumstances derived from the country’s independence led to the balancing of forces, which in turn catalysed the assumption of the social costs of oil operations and the economic development around production areas. Second, with the rise of oil activity, the balance of power became highly biased, favouring a dominant elite coalition that exposed populations to social costs. Third, the mobilisation of non-elite organisations exhausted the last military regime, opening political and economic access to more Nigerians. The authorities that took over from 1999 became more politically open and turned into international sustainable development and corporate social responsibility movements [12].

Companies operating next to communities (onshore) such as Total, Shell, and Nigerian Agip Oil Co. are gradually implementing Memorandums of Understanding (MoU), i.e. non-binding commitments signed for three to five years with representatives of local communities to define expectations on both sides. Consequently, businesses expect an uninterrupted production cycle, while people ask for the social costs of activity and local development projects to be covered. Commitments taken by the companies consist of projects of transport infrastructure (roads, bridges, berths, etc.), health (health centres, sanitary facilities), education (classrooms, vocational training centres, teacher housing, teaching materials), social (party rooms, community homes, sports fields), water supply (wells, water bores, etc.).

All this also encompasses targets in local jobs, permanent payments to landowners who have given over resource-holding lands, scholarships and training for small trades, entrepreneurship support, periodic health campaigns, and support for cultural, sporting, educational or professional events. For Shell, Nigeria’s largest oil producer, such a commitment reached US$112 million in 2014, excluding the direct cost of pollution and accident management.

The path to open political and economic access to all Nigerians depends on the changing dynamics of power balance between elites and non-elites. The social responsibility of oil and gas corporations and other significant organisations is also part of these dynamics. Such an approach does not stand in the way of the conventional normative system. Still, it supports the hypothesis that an analysis of the dynamics of power relations and, if necessary, an adjustment of power imbalances between parties are required to create the conditions conducive to the well-being shared among all stakeholders.

4 Major Social Responsibility Frameworks

4.1 United Nations Global Compact

The UN Global Compact is the self-proclaimed world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative. It is a call to companies to take actions that foster societal goals by means of aligning strategies and operations with universal principles on human rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption [13]. In other words, the UN is helping partner companies to do business in ways that benefit society and protect people. Beyond respecting rights, adherents businesses are expected to take additional steps towards improving the lives of the people they affect, such as by creating quality jobs, products and services that help meet basic needs, and more inclusive supply chains. Firms within the program are also likely to make strategic social investments that support social sustainability and partner with other local businesses, merging strengths to create a more significant positive impact.

Further, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasise women’s empowerment as an essential development objective, in and of itself. Extractive companies that focus on women’s empowerment experience better business performance. Investing in women and girls can increase organisational effectiveness, productivity, return on investment and higher consumer satisfaction. Similar principles embroil children and Indigenous peoples to help ensure that current and future projects enjoy conditions to make stable and productive societies.

Sakhalin Energy programs on the preservation of indigenous culture in Russia and Al Baraka Banking Group actions for patronage and sponsorship of educational and social projects [14] are two featured cases of successfully implementing the Global Compact initiative.

4.2 Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)

EITI is the global standard to bolster the open and accountable management of extractive resources, namely oil, gas and mineral resources. The standard requires the disclosure of information from the point of extraction along the extractive industry supply chain, how revenues flow on the government and how they benefit the public. Guided by the belief that natural resources from a territory belong to its citizens, EITI combats poor natural resource governance that often leads to corruption and conflict.

The latest EITI Standard 2019 consists of two chapters and 12 sections [15]. It outlines the requirements applicable to countries implementing the standard and the Articles of Association governing the EITI. Eight conditions form the core of the EITI Standard. We are highlighting the most relevant in the following bullet points:

- Oversight by the multi-stakeholder group;

- Transparency in information about exploration activities, production data, and export data;

- Social and economic spending;

- Outcomes and impact seeking to ensure that stakeholders are engaged in dialogue.

The EITI Requirement 3 calls for disclosures of information related to exploration and production and is one of the document’s key sections. Moreover, it covers artisanal and small-scale mining. Guidance on Requirement 3 tells implementing countries to disclose significant exploration activities, production volumes and values by commodity. This data should be further disaggregated by region, company or project.

Figure 5. Overview on how countries are progressing towards meeting the EITI Standard: Yet to be assessed against the Standard (blue), Satisfactory progress (dark green), Meaningful progress (light green) Inadequate progress / suspended (yellow). Source: https://eiti.org/countries

4.3 Benefit Corporations and Certified B Corporations

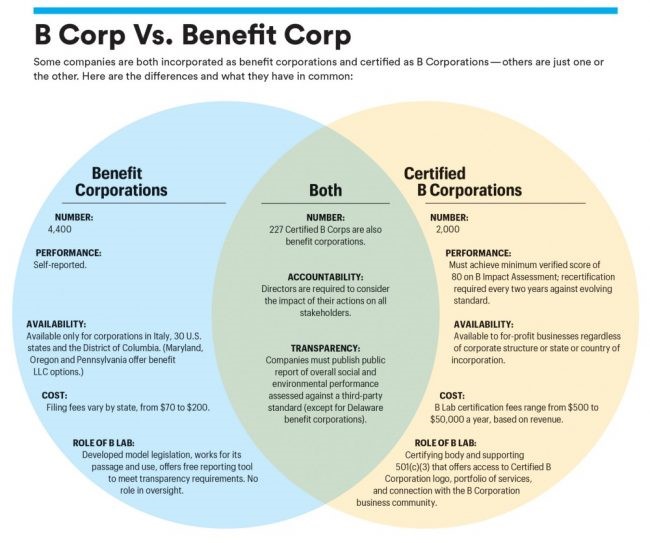

These two kinds are often confused. They have a lot in common and complement each other, but they have a few major differences.

The B Corp Certification is a third-party certification issued by the non-profit B Lab, based in part on a company’s proved performance on the B Impact Assessment [16]. A B Corp is subjected to this independent assessment of its impact on communities, people, and the environment. That independent assessment is rigorous, it may comprise over 400 questions, and it takes a long process to get there. Just to give an idea of some of the topics that the assessment covers: they have sections on anti-corruption within the target company; questions about its supply chain and ethical sources; questions about how it pays employees and the diversity of its staff; questions about customer stewardship, warranties and customer satisfaction.

The benefit corporation is a legal structure for a business, like an LLC, and is officially empowered to pursue positive stakeholder impact alongside profit [17]. Benefits corporations result from a new generation of value-driven consumers and shareholders demanding that corporations deliver benefit to their communities. There are ten essential characteristics of a benefit corporation [2]. Among them, a core commitment to a social purpose which is rooted in the organisational philosophy and structure; equitable compensation of all stakeholders in proportion to their contribution and risk; pledge to create net positive social and environmental impacts; and commitment to open assessments and reporting of social, environmental, and financial indicators.

Combio Energia in Brazil, Urban Mining in Florida (US), and Cerco Construction Company in Chile are some examples associated with oil, gas, energy, and mining within this initiative. Some companies are both Certified B Corporations and benefit corporations, and the benefit corporation structure fulfils the legal accountability requirement of B Corp Certification. The two types are both the classic examples of seeking benefits not only for shareholders but also for all stakeholders.

Figure 6. Differences and coincidences between B Corp and Benefit Corporations. Source: https://www.corpgov.net/2018/02/benefit-corporation-accountability-matters/

4.4 Social Responsibility through ‘Social Licence to Operate.’

The concept of a ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) emerged in the 1990s to alleviate conflicts between local communities and businesses in the mining industry [18]. It gained popularity as one way in which ‘‘social’’ considerations and demands from the local population, such as a greater share of benefits and more involvement of local representatives in the decision-making process, can be addressed. Increased stress on ‘Sustainable Development’ where non-state actors are perceived to have an essential role in governance decision-making contributed to the adoption of SLO. Recently, SLO has grown in notoriety within different business segments, including manufacturing, agriculture, transport, pharmaceutical, energy, and telecommunication.

The core of SLO is the concept of social recognition of business in that it emphasises the need to change the relationship between the economy and society. The economic process is regarded as consisting of social relations, shared rules, and beliefs, businesses developing as an embodiment of social purpose. For that reason, an industry must receive social recognition to establish legitimacy. This concept is not aligned with the demand for business self-regulation. One should interpret laws on public health, work conditions, union rights, social insurance, and public utilities as countervailing measures to control industries’ power over society.

Through SLO, collective dimensions in governance received increase focus to catch a balance between local expectations and companies’ budgets. In fact, some countries have assimilated these concepts in corporate legislation, including developing countries such as India. Some states — e.g. United Kingdom, Australia — incorporate details of directors’ responsibility that were traditionally enforced under common-law and fiduciary duties. This happens because, under the lens of social license, directors must protect the larger community’s interests, which is also incorporated into corporate policies and affirmed by various jurisdictions worldwide. Benefit Corporations Model in the United States (see Section 4.3) are another example of SLO.

5 Conclusion

In search of conditions for successful development of social responsibility practices for extractive industries, this article’s ambition was to analyse the behavioural dynamics of oil and gas, mining, and other extractive corporations concerning the social, cultural, and institutional environments in which they operate. Effective regulations for responsible actions depend not only on intrinsic traits but also on the host environment where they are applied. This scenario is exacerbated for natural resource extracting transnational corporations and developing countries.

Large extractive projects can and do make a positive contribution to human rights, particularly facilitating employment and income for local communities, with all the associated benefits for economic and social rights that such wealth brings. Extractive industries recurrently strengthen human rights by providing infrastructure and other social programs in the local community. However, participation in human rights abuses is also well documented.

We assume that a global social responsibility standard on extractive activities would consist of mechanisms to combat predation based on the Sustainable Developments Goals and Corporate Social Responsibility standards, strategies, and tools. Some of the now existing standards, like the Global Compact, the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative, or third-party certifications for extractive industries, have paved the way towards more effective and operational tools.

6 References

[1] North, D., Wallis, J., & Weingast, B. (2009). Violence and social orders. A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Rahim, M. M. (Ed.). (2019). Code of Conduct on Transnational Corporations: Challenges and Opportunities. Springer.

[3] https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-truth-about-csr

[4] Tysiachniouk, M. S., & Petrov, A. N. (2018). Benefit sharing in the Arctic energy sector: Perspectives on corporate policies and practices in Northern Russia and Alaska. Energy Research & Social Science, 39, 29-34.

[5] Henry, L. A., Nysten-Haarala, S., Tulaeva, S., & Tysiachniouk, M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and the oil industry in the Russian Arctic: Global norms and neo-paternalism. Europe-Asia Studies, 68(8), 1340-1368.

[6] Wanvik, T. I. (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility-re-territorialisation of global business. Grounding foreign companies in local context through CSR-the case of Norwegian (Master’s thesis, The University of Bergen).

[7] https://pubs.spe.org/en/hsenow/hse-now-article-page/?art=7413

[8] Dashwood, H. (2012). The Rise of Global Corporate Social Responsibility: Mining and the Spread of Global Norms (Business and Public Policy). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139058933

[9] Dominish, E., Florin, N., & Teske, S. (2019). Responsible minerals sourcing for renewable energy. Report prepared for Earthworks by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

[10] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/anvil-mining-lawsuit-re-dem-rep-of-congo/

[11] Adam McBeth, Crushed by an Anvil: A Case Study on Responsibility for Human Rights in the Extractive Sector, 11 Yale Hum. Rts. & Dev. L.J. (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yhrdlj/vol11/iss1/8

[12] Hervé Lado, « Les responsabilités sociétales dans l’histoire de l’exploitation pétrolière au Nigeria », Mondes en développement 2017/3 (n° 179), p. 103-118. DOI 10.3917/med.179.0103

[13] https://www.unglobalcompact.org/

[15] https://eiti.org/document/eiti-standard-2019#r3

[16] https://bcorporation.net/

[17] https://benefitcorp.net/

[18] Prno, J., & Slocombe, D. S. (2013). A Systems-Based Conceptual Framework for Assessing the Determinants of a Social License to Operate in the Mining Industry. Environmental Management, 53(3), 672–689. doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0221-7

To all knowledge

To all knowledge