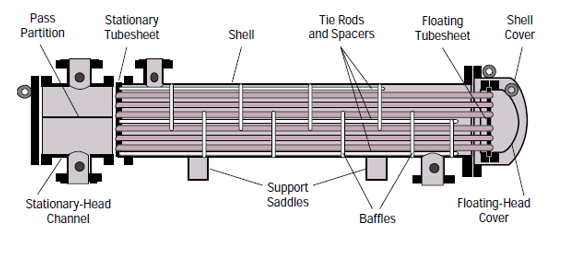

1. Introduction to Design of Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger

Design of shell and tube exchanger: A shell and tube heat exchanger is one of the most popular exchangers due to its flexibility. In this type, there are two fluids with different temperatures; one flows through the tubes and the other flows through the shell. Heat is transferred from one fluid to another through the tube walls, either from the tube side to the shell side or vice versa. This system handles fluids at different pressures; higher pressure fluid is typically directed through tubes, and lower pressure fluid is circulated through the shell side.

Figure 1: Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger

2. Construction Details

2.1 Shell

The shell is constructed from pipe up to 24 inches or rolled and welded plate metal. Low carbon steel is standard for economic reasons, but other materials suitable for extreme temperatures or corrosion resistance are often specified. Using commonly available shell pipes with 24-inch diameter reduces cost and ease of manufacturing, partly because they are generally more perfectly round than rolled and welded shells. Roundness and consistent shell inner diameter are necessary to minimize the space between the baffle outside edge and the shell, as excessive space allows fluid bypass and reduces performance.

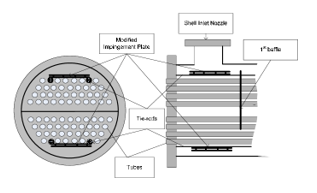

In applications where the fluid velocity for the nozzle diameter is high, an impingement plate is specified to distribute the fluid evenly to the tubes and prevent fluid-induced erosion, cavitation, and vibration. An impingement plate can be installed inside the shell, eliminating the need to install a full tube bundle, which would provide a less available surface. The impingement plate can be installed in a domed area (either by reducing coupling or a fabricated dome) above the shell. This style allows a full tube count and maximizes utilization of shell space.

Figure 2: Impingement Plate in Tube Layout

2.2 Channels (Heads)

The channel type is selected based on the application. Most channels can be removed to access the tubes. The most commonly used channel type is the bonnet. It is used for services that do not require frequent channel removal for inspection or cleaning. The removable cover channel can be flanged or welded to the tube sheet. The removable cover permits access to the channel and tubes for inspection or cleaning without removing the tube side piping.

The rear channel is often selected to match the front channel. For example, a heat exchanger with a bonnet at the front head (B channel) will often have a bonnet at the rear head (M channel) and be designated as BEM. Pass partitions are required in channels of heat exchangers with multiple tube passes. The pass partition plates direct the tube side fluid through multiple passes.

2.3 Tubes

Tubes are generally made seamless or welded. Seamless tubing is produced in an extrusion process; welded tubing is produced by rolling a strip into a cylinder and welding the seam. Tubes are made from low carbon steel, stainless steel, titanium, Inconel, Copper, etc. Standard tube diameters of 5/8 inch, 3/4 inch, and 1 inch are preferably used to design compact heat exchangers. Tube thickness should be maintained to withstand:

1) Pressure on the inside and outside of the tube

2) The temperature on both the sides

3) Thermal stress due to the differential expansion of the shell and the tube bundle

4) Corrosive nature of both the shell-side and the tube-side fluid.

The tube thickness is expressed in terms of BWG and true outside diameter (OD). Tube lengths of 6, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 feet are commonly used. Longer tubes reduce shell diameter at the expense of higher shell pressure drops. Tubes of larger diameter are sometimes used to facilitate mechanical cleaning or achieve lower pressure drop. A maximum number of tubes in the shell increases turbulence, which increases the heat transfer rate. Finned tubes are also used when fluid with low heat transfer coefficient flows in the shell side.

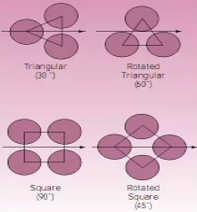

2.4 Tube Sheet

Tube sheets are made from a round flat piece of metal with holes drilled for the tube ends in precise locations and patterns relative to one another. Generally, the tube sheet material is the same as the tube material. Tubes are appropriately attached to the tube sheet, so the fluid on the shell side is prevented from mixing with the fluid on the tube side. The tubes are inserted through the holes in the tube sheets and held firmly in place by welding, mechanical or hydraulic expansion. A rolled joint is the common term for a tube-to-tube sheet joint resulting from a mechanical expansion of the tube against the tube sheet. Holes are generally drilled in the tube sheet in either of two patterns, triangular or square.

Figure 3: Tube sheet

2.5 Tube Pitch

The distance between the centres of the tube hole is called the tube pitch; it is typically taken as 1.25 times the tube’s outside diameter. The minimum value is restricted to 1.25 because the tube-sheet ligament (a ligament is the portion of material between two neighbouring tube holes) may become too weak to roll the tubes into the tube sheet properly. Other tube pitches reduce the shell side pressure drop and control the shell side fluid’s velocity as it flows across the tube bundle. Triangular pitch provides higher heat transfer and compactness. Square pitch facilitates mechanical cleaning of the outside of the tubes.

Figure 4: Types of Tube Pitch

2.6 Baffles

Baffles serve the following functions:

1) Support the tubes during assembly and operation

2) Prevent vibration from flow-induced eddies and maintain the tube spacing

3) Direct the flow of fluid in the desired pattern through the shell side.

A segment, called the baffle cut, is cut away to permit the fluid to flow parallel to the tube axis as it flows from one baffle space to another. The spacing between baffles is called the baffle pitch. The baffle pitch and the baffle cut determine the cross-flow velocity, heat transfer rate and pressure drop.

The orientation of the baffle cut is essential for the heat exchanger installed horizontally. The baffle cut should be horizontal when the shell side heat transfer is sensible heating or cooling with no phase change. This causes the fluid to follow an up-and-down path and prevents stratification with warmer fluid at the top of the shell and cooler fluid at the bottom. For shell-side condensation, the baffle cut for segmental baffles is vertical to allow the condensate to flow towards the outlet without significant liquid holdup by the baffle. The baffle cut may be vertical or horizontal for shell-side boiling, depending on the service.

The cut areas represent 20 to 25% of the shell diameter for most liquid applications.

Figure 5: The orientation of Horizontal and Vertical Baffles

2.7 Tie Rods and Spacers

Tie rods hold the baffle in place with spacers, tubing or pipe placed to maintain the selected baffle spacing. The tie rods are screwed into the stationary tube sheet and extend the bundle’s length to the last baffle. Tie rods and spacers may also be used as sealing devices to block bypass paths due to pass partition lanes or the clearance between the shell and the tube bundle. The minimum number of tie rods and spacers depends on the shell’s diameter and the size of the tie rod and spacers.

3. Design of Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger: Codes and Standards

Code rules and standards aim to achieve minimum requirements for safe construction and provide public protection by defining those materials, design, fabrication, and inspection requirements; ignoring this may increase operating hazards. Following are some mechanical design standards and pressure design codes used in heat exchanger design:

1) TEMA standards (Tubular Exchanger Manufacturer Association., 1998)

2) HEI standards (Heat Exchanger Institute, 1980)

3) API (American Petroleum Institute)

4) ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers)

4. TEMA Designations

To understand the shell and tube heat exchanger’s design and operation, it is important to know the vocabulary and terminology used to describe them. This vocabulary is defined in terms of letters and diagrams. The first letter describes the front header type, the second letter the shell type, and the third letter the rear header type. For example, BEM, CFU, and AES.

TEMA has classified the front head channel and bonnet types according to the letters (A, B, C, N, D). The shell is classified according to the nozzle locations for the inlet and outlet. There is a type of shell configuration (E, F, G, H, J, K, X). Similarly, the rear head is classified (L, M, N, P, S, T, U, W).

Fig 6: TEMA Designation

5. General Design Considerations

5.1 Fluid Allocation

- High-pressure streams should be located on the tube side.

- The corrosive fluid is placed on the tube side.

- Stream exhibiting the highest fouling should be located on the tube side.

- More viscous fluid should be located on the shell side.

- Lower the flow rate, the stream should be placed on the shell side.

- Consider finned tubes when the shell side coefficient is less than 30% of the tube side coefficient.

- Do not use finned tubes when shell-side fouling is high.

- Stream with a lower heat transfer coefficient goes on the shell side.

- Toxic fluid should be placed on the tube side.

5.2 Shell and Tube Velocity

High velocities will yield high heat transfer coefficients and a high pressure drop, causing erosion. The velocity must be high enough to prevent any suspended solids settling, but not so high as to cause corrosion. High velocities will reduce fouling. Plastic inserts are sometimes used to reduce erosion at the tube inlet. Typical design velocities are given below:

LIQUIDS

Tube-side process fluid: 1 to 2 m/s

Shell-side: 0.3 to 1/m/s

VAPORS

The velocity used for vapours will depend on the operating pressure and fluid density; the lower values in the range given below will apply to molecular-weight materials.

Vacuum: 50 to 70 m/s

Atmospheric pressure: 10 to 30 m/s

High pressure: 5 to 10 m/s

5.3 Stream Temperature

The closer the temperature approach used (the difference between the outlet temperature of one stream and the inlet temperature of the other stream), the larger the heat transfer area required for a given duty. The optimum value will depend on the application and can only be determined by economically analysing alternative designs. As a general guide, the greater temperature diff should be at least 20 °C and the least temperature diff 5 to 7 °C for cooling using cooling water and 3 to 5 °C using refrigerated brine. The maximum temperature rise in recirculated cooling water is limited to around 30°C. Care should be taken to ensure that cooling media temperatures are kept well above the freezing point of the process materials. When heat exchange is between process fluids for heat recovery, the optimum approach temperatures will typically not be lower than 20°C.

5.4 Pressure Drop

The value suggested below can be used as a general guide and usually gives designs near the optimum.

LIQUIDS

Viscosity<1 mN s/m2, ΔP=35 kN/m2

Viscosity=1 to 10mN s/m2, ΔP= 50-70 kN/m2

GAS AND VAPORS

High vacuum: 0.4-0.8 kN/m2

Medium vacuum: 0.1 x absolute pressure

1 to 2 bar: 0.5 x system gauge pressure

Above 10 bar: 0.1 x system gauge pressure

When a high-pressure drop is utilized, care must be taken to ensure that the resulting high fluid velocity does not cause erosion or flow-induced tube vibration.

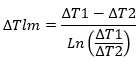

6. Design Procedure: (KERN method)

- Obtain the Physical properties for both the fluids.

- Heat load, Q = m*Cp*∆t

- Calculate LMTD (Log Mean Temperature Difference)

Where,

T1, T2 = Inlet and Outlet temperatures of hot fluid

t1, t2 = Inlet and Outlet temperatures of cold fluid

- Determine temperature correction factor FT ([1] page 828-833 Figs. 18-23). FT normally should be greater than 0.75 for the steady operation of the exchangers

- True Temperature Difference

∆t = FT*∆TLMTD

- Assume a reasonable value of the overall heat transfer coefficient Ud (assumed). The value of Ud (assumed) concerning the process hot and cold fluids can be taken from the book ([1] page 840 Table 8.)

- The total surface area of tubes,

![]()

- The surface area of one tube,

A’= π* do *L

Where,

do = Tube outside diameter

L = Length of tube

- Number of Tubes,

![]()

- The baffle spacing is usually chosen to be within 20 % -100% of the shell inside diameter.

- Clearance, C = Pt – do

Where,

Pt = Pitch

6.1 Shell Side Calculations

- Shell Area,

![]()

- Mass velocity,

![]()

Where,

Ms = Fluid flow on the shell side

Ds = Shell inside diameter

- Caloric Temperature (find physical properties at this temperature),

![]()

- Equivalent diameter for square pitch

![]()

- Calculate Reynolds Number,

![]()

- Find JH from the graph between Re and JH ([1] page 838). Using that value calculate the Shell side heat transfer Coefficient ho,

![]()

Where,

k = thermal conductivity

![]() = dynamic viscosity of the water fluid

= dynamic viscosity of the water fluid

![]() = shell fluid dynamic viscosity at the average temperature

= shell fluid dynamic viscosity at the average temperature

De= equivalent diameter of shell side

C = specific heat of the shell side fluid

6.2 Tube Side Calculations

- Flow Area,

![]()

- Mass velocity,

![]()

Where,

Mt= Fluid flow on the tube side

- Calculate Reynolds Number,

![]()

- Find JH from the graph between Re and JH ([1] page 834). Using that value, calculate the tube side heat transfer coefficient hi

![]()

Where,

k = thermal conductivity

![]() = dynamic viscosity of the water fluid

= dynamic viscosity of the water fluid

![]() = tube fluid dynamic viscosity at the average temperature

= tube fluid dynamic viscosity at the average temperature

di = inside diameter of tube side

C = specific heat of the tube side fluid

![]()

- Calculate the tube outside heat transfer coefficient,

![]()

Where,

Ro = outside dirt coefficient (fouling factor)

Ri = inside dirt coefficient (fouling factor)

- Check this condition for accurate design,

![]()

6.3 Pressure Drop Calculations

- Shell Side

![]()

Where,

ΔPs pressure drop for shell side

N+1= number of crosses = Tube length / Baffle spacing

Ǿs= viscosity correction factor for shell-side fluid

f = Friction factor

- Tube Side

![]()

Where,

ΔPt = pressure drop for tube side

n = number of passes

L = length of the tube

Ǿt= viscosity correction factor for tube side fluid

f = Friction factor

- Return pressure loss (due to change in the flow direction of the tube side fluid)

![]()

Where,

s = Specific gravity of the fluid

g = acceleration due to gravity

n = number of passes

v2/2g = velocity head

- Total tube side Pressure,

![]()

7. References

[1] D. Q. Kern, “Process Heat Transfer”, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Int. ed. 1965.

[2] Thulukkanam Kuppan, “Heat Exchanger Design Handbook”, First Edition, Marcel-Dekker, (2000).

[3] Saunders, E. A. D. (1988) Heat Exchangers “Selection, Design, and Construction”, Longman Scientific and Technical. DOI: 10.1016/0378-3820(89)90046-5

[4] NPTEL – Chemical Engineering – Chemical Engineering Design – II

[5] R.K. Sinnott, Coulson & Richardson’s Chemical Engineering Design, Volume 6, 3rd Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann

About EPCM

To all knowledge

To all knowledge